Född 1771 29/5, död under finska kriget 1808-09.

Fältväbel vid Åbo läns infanteriregemente. Kartograf och gravör.

.

Bland arbeten.

Karta över Skagshamn jämte stilprov.

Hultmark, 1944.

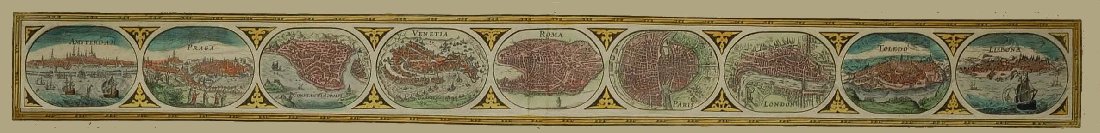

Ca. 1550. Han föddes i Venedig 1515

Italiensk författare. Hade under årens lopp en rad höga förtroendeposter i republiken Venedig. 1543 deltog han i beskickningen till kejsare Karl V. Han hade vunnit rykte som författare, matematiker och geograf, då han 1558 utgav en reseberättelse från de nordiska farvattnen, byggd på gamla familjeupptäckter. Enligt dessa vistades två bröder från Venedig, Nicolo och Antonio Zeno, under åren runt 1390 på ön Frisland mellan Skottland och Grönland och utförde stora bedrifter i tjänst hos landets furste, Zichmni. Med berättelsen om de två brödernas resor i det nordliga Atlanten som underlag utarbetade Zeno en karta som medföljde boken. Här är Frisland och en rad andra okända öar ritade med stor noggrannhet. På grund av författarens anseende blev boken accepterad av samtiden men efter hand som kunskapen om dessa farvatten ökade, och det visade sig att de sjöfarande aldrig återkom, började man tvivla på sanningen i berättelsen. Under flera år har lärda, vetenskapsmän, geografer och historiker gjort Zenos bok till f...

Bagrow. - Salmonsen.

1512-1577.

Cartographer, publisher and printer of maps and graphic art. Born in France, Lafreri moved to Rome in 1540 where he launched a business in 1544. His great triumph came in 1572 with the publication of a catalogue including a reduced copy of Olaus Magnus's famous Carta Marina.

Sveriges sjökartor – A. Hedin.

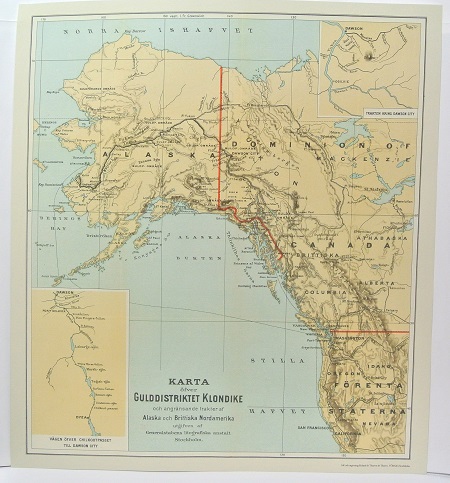

Gulddistriktet Klondike - ca 1897.

'Amérique ou Indes Occidentales...' - Robert de Vaugondy 1778.

Olaus Magnus text till den berömda kartan "Carta Marina".

Texten finns även på katalanska, spanska och engelska.

Bureus karta över norden

Kartor och atlaser

Bilder och planschverk

Teckenförklaringar

"The History of Globe Making."

by Peter van der Krogt.

Map historian, Explokart Research Program, University of Utrecht, The Netherlands.

“Now what is named Sphaera inGreeke, and Kloot in Duytsche ( Dutch), that now in Latine is Globus. Latine being soo well understood, we will not discern betwixt the two Names. Men of Mathesis define the Globus as a round solid body, having every part of the surface equally distant from a point withinne (…). Such are our Globus that they represent in reduced forme, like men of Architecture a noble abode. God’s wondrous World and the Heavens, not because thesein themselves are spherical, but while they bring a true depiction of all the Stars and the Constellations and all of the Lands, Island and Oceans.”

This is what the celebrated cartographer and globe maker Willem Jansz. Blaeu (1571-1638) writes in the introduction to the manual which accompanied his globes. He refers to both the celestial and the terrestrial globe as it was common practice in his time to make and sell globes as pairs. Both have the same diameter and are mounted in identical stands.

This practice of selling pairs continued well into the 19th century, when the production and sale of terrestrial globes as individual items took the upper hand. Today, terrestrial globes are being produced in large numbers, while modern celestial ones are hard to find.

In early times, globes served as auxiliary instruments for astronomical calculations and observations; later on, the uniformity of the representations of earth and heaven became more important.

Mapmakers are confronted with the age-old problem of how to represent the details of a curved image on a flat (paper) surface. Terrestrial globes have a huge advantage over “normal” maps: the reproduction of the curved image can be achieved without too much distortion.

A disadvantage of globes, however, is that, depending on the scale of the map, they become difficult to use. The diameter increases so substantially in relation to the scale that they become impractical. A common diameter is that of approx. 30.5cm. (12in) which translates into a scale of 1:40,000,000.

The terrestrial globe present a reduced image of the earth; the celestial globe “the vault of the heavens”, or firmament. Today we know that the universe is not a sphere and that the distances between stars are almost unimaginable, although observed from earth they appear to be quite “close” to each other. These facts, however, were not known in the past. The stars were supposed to be positioned on a large sphere, the firmament. Within this concave space the earth, sun, moon and planets are located. The stars on the sphere are gathered in the form of constellations, which carry names derived from mythology.

On celestial maps and globes from the 16th and 17th centuries in particular, the constellations were drawn in such abundant detail and were so beautifully coloured that it is difficult to distinguish the stars.

The celestial globe is the representation of the firmament as seen from a position outside the sphere. This results in the constellations being mirrored: human figures therefore are seen with their backs turned to the observer. In manuals and literature, the positions of the stars were defined by the place within the body of the constellation, e.g. in the left arm of Orion. Should the images have been drawn as we see them, this would have led to confusion.

From the late 16th well into the 18th century, pairs of globes in the first place were made to facilitate astronomical calculations and to demonstrate a range of astronomical problems for educational purposes. For this reason, almost all globe-makers published manuals. In these manuals, both the Ptolemaic (sun revolves around a static earth) and Copernican (earth around static sun) systems were dealt with as both systems had their follower. This explains why Blaeu’s manuals is entitled “Tweevoudigh Onderwijs…” (“Dual Instruction…”): it could be sold to all astronomers without going into separate editions.

The Productions of Globes

Virtually all materials which are suitable for being processed into the form of a sphere have been used to make globes: wood, gold, silver, copper, ivory, glass &c. These materials allowed for the map to be drawn, painted or engraved on the sphere. For commercial purposes, however, these materials and techniques were far too expensive.

Less expensive materials like paper and plaster were used for the construction of the sphere (or two hemispheres) on which the printed map was pasted down. Construction started by making the axis, a cylindrical wooden rod. To the tips a large number of “felty” segments of “orange peel” form were nailed and various layers were joined by soaking these with water and starch. This process resulted in a rather firm sphere, which covered with a thin layer of plaster. The plaster was than sanded until a perfect sphere was obtained. The “skin” of the sphere is relatively thin: approx. 0.5cm. for Blaeu’s globes of 23cm. diameter. The map was printed on paper in twelve or more gores. A mirror image of the map’s elements was engraved on a copper plate. The translation of the map into segments required great expertise to ensure a perfect fit on the globe’s surface. The sphere was mounted into a brass meridian (engraved with a graduation in degrees on one side of it) and attached to the axis at the poles. At brass hour ring was placed at the North Pole and an hour pointer attached to the axis. This unit is then mounted in a wooden stand with a construction to allow the meridian ring to be positioned under whatever angle is required and to allow the sphere to revolve around its axis. The columns of the stand support a wooden horizon circle, which is covered with printed paper circle containing various details such as the signs of Zodiac, the months of the year, wind directions and graduations. To establish which stars are visible from where you are, one would position the celestial globe at the geographical latitude of your location. That part of the globe which is above the horizon circle shows the visible stars. By revolving the globe, all stars that will become visible from where you are can be observed.

The Oldest Globes:

Greek and Arabic globes

The first globe to be made was most likely a celestial one, the reason being that to the human eye the earth does not look like a sphere at all, while the sky appears to us as concave hemisphere. That this hemisphere is continued around the earth to form a full sphere is a matter of logical deduction. The Greek mathematician Eudoxus of Cnidos (400-347 BC) was probably the first to make a reproduction of the sky on a sphere. Claudius Ptolemaeus (150 AD) plays an important role in the history of globe-making. In two books he recorded the geographical and astronomical knowledge of his time. In the “Geographia” he lists the geographical positions of some 8,000 places, in the “Almagest” of over 1,000 stars and 48 constellations. The Almagest in particular has been instrumental for the construction of celestial globes for a very long time.

Two celestial globes have been preserved from antiquity: the “Atlas Farnese” which can be regarded as a decorative object, and the “Mainz Globe” which is a more practical one. The Farnese Globe, a statue of Atlas carrying the globe, has a diameter of 65cm. and in relief shows the shapes of the constellations, the ecliptic, the equator, the tropics and the colures. There are no stars on it. The reproduction of the vernal equinox is in accordance with that in the Almagest (150 AD), dating the statue after that point in time.

The Mainz Globe, with a diameter of 11cm. and all 48 constellations (even if they not fully agree with the Almagest), is the only complete celestial globe remaining from antiquity. It is a work from the Roman Empire of between 150 and 220 AD and supposedly originated in Asia Minor.

It may be taken for certain that the ancient Greeks made terrestrial globes as well. In the third century BC, geographer Erathostenes calculated the circumference of the earth with the help of the angel of incidence of the solar rays. His findings vary only slightly from the correct circumference. It is easy to calculate the surface area of the earth from the circumference. The Greek geographers, who were familiar with the Mediterranean area, thus found that only a minor part of the earth was known to them. There was no need to make a terrestrial globe, as this would have to remain blank for the greater part, or be filled with hypothetical lands.

The Arab civilisation in the early Middle Ages became inspired by Ptolemy in particular to make celestial globes. There is no record of terrestrial globes.

Astronomy, supported by celestial globes, played an important role in Christian science because it offered the only correct method for the computation of time, which in turn was important to establish the Christian holidays. It goes without saying that in Western Europe abbeys were the first to own celestial globes. The oldest of these globes, dating from circa 1400 and made of wood covered with linen on which the constellations are drawn in ink, was bought by a member of the clergy in 1444.

The oldest terrestrial globe: Martin Behaim’s globe of 1492

In the year in which Columbus reached the New World, the oldest known terrestrial glob was made. The patrician and businessman Martin Behaim (1459-1506), citizen of Nuremberg, commissioned his globe from a local craftsman and a painter. The globe was to serve as an inspiration for his fellow citizens because he tried to raise funds for an expedition to China. The globe, which for more than 500 years has been, and still is, kept in the city where it was made, is a very important object for two reasons: it is the first terrestrial globe made in “modern” Europe and it is the oldest globe still in existence. The so-called “Erdapfel” has a diameter of 51cm. and is made of paper and plaster. The sphere is covered with twelve vellum gores on which the map has been painted. The map follows the Geographia of Ptolemy to a large extent, but the coastlines of Europe and of West Africa are represented according to the latest discoveries. Naturally the American continent is lacking.

Well into the 20th century, the city of Nuremberg housed a number of important globe-makers. In the southern area of Germany and adjacent countries, the making of terrestrial and celestial globe flourished at the turn of the 15th and 16th century.

The first printed globes

All of the above mentioned globes are unique objects. Their method of construction and decoration was time-consuming and costly. The growing interest in geography and the impact of the printing press resulted in a method to reproduce the cartography of the globe by drawing the map, divided over twelve slanting segments, the gores, each of which cover an area of 30 degrees of longitude. The map was than mirrored, engraved into a copper plate and printed on strong paper. The invention of this method of reproduction is generally attributed to Martin Waldseemüller (ca. 1475-1518/21), but Francesco Roselli (1445-1510), printer of maps in Florence, may have been the first to have printed globe gores.

The influence of the publications of Waldseemüller on the development of cartography is monumental. His large map of the world is the first to portray America, the name of which he derived from that of Amerigo Vespucci. America also figures on his far smaller globe gores.

Johann Schöner from southern Germany was the first to publish (1515) a pair of globes, modelled after Waldseemüller.

The Netherlands as the center of globe production

The political and economic situation at the end of the 16th century resulted in Amsterdam becoming the centre of cartography par excellence in Europe (and thus: of the world). This status would continue throughout during the better part of the 17th century. Gemma Frisius and Gerard Mercator created the basis for its monopoly in the southern part of Netherlands. The families of Hondius-Janssonius and Blaeu dominated the market for globes. Their output was considerable and standard of quality of their products was very high indeed. The firm of the Van Langrens was less well known, but was relatively important in Amsterdam.

The first globe makers in Netherlands

Around 1520 the demand for globes in Netherlands increased such that the sole supplier, Johann Schöner, was unable to meet it. Roeland Bollaert, an Antwerp bookseller with an interest in geography and astronomy, decided to start the production of globes and publish an accompanying manual. The technical side of the production was negotiated with Gaspard van der Heyden, a goldsmith of Louvain. Franciscus Monachus, a scholar from Mechelen, designed the map of the terrestrial globe. The celestial globe and the manual were copied from Schöner. The terrestrial globe and its manual were published in about 156, The celestial drawn for 1527. Unfortunately, no copies survive of the first pair produced in the Netherlands.

The founding father of a scientific approach to geography and cartography at Leuven is Gemma Frisius (1508-1555), a man of science originating from Friesland. Supposedly by order of Bollaert he produced a terrestrial globe, with a diameter of approx. 37cm. in 1529, accompanied by a book entitled (in translation) “On the basic principles of astronomy and cosmography”. Gaspard van der Heyden again made the globe. No copies of this globe have survived either. At around 1536 Frisius produced a second edition of his terrestrial globe, and in 1537 the matching celestial one. Of this oldest Dutch pair of globes a few copies have survived.

The famous cartographer Gerard Mercator (1512-1594) may be regarded as the founder of modern globe-making and production, as well as of commercial map production in general. He acquired his knowledge as a pupil of Frisius, and also received training in engraving and the making of scientific instrument. His competence in this area was such, that Frisius had him engrave the plates for the latter’s second edition of his pair of globes. It is on these globes that Mercator’s name appears for the first time. Although Mercator would have preferred not to make maps but devote his time to his scientific interests, he was forced to make and publish maps and globes to support his family.

After completing a series of maps, Mercator started the construction of a terrestrial globe. He was not content with the manner in which most geographers dealt with the Portuguese discoveries in South-East Asia, which were in conflict with the Ptolemy’s view of the world. With his globe, Mercator endeavoured to demonstrate that the new discoveries could be fitted into the Ptolemaic view, but this must be regarded as ineffective: the “other geographers” were right in abandoning Ptolemy. A further innovation in Mercator’s globe was that he made it appropriate for navigation. He included loxodromes (which already appear on the oldest type of sea maps, the Portolans) to be used to determine the course at sea. Theoretically, the undistorted view of the world on a globe is ideal and much better than that on a flat sheet of paper, whose distortions could mask the right track.

A globe, however, causes more problems than anticipated as it proved to be difficult to measure distances or determine a course on a curved surface. Nor is a globe large enough to contain sufficient detail or small sturdy enough to use aboard a rocking vessel at sea. In spite of these disadvantages the people on shore regarded the globe as an instrument of navigation, which made the globe a symbol of shipping and seamanship.

Mercator’s terrestrial globe with a diameter of 41cm. came onto the market in 1541. The diameter translates into a scale of approx. 1: 30,000,000 which is not a measure for comfortable navigation.

The celestial globe followed in 1551. The globes were always sold as a pair. Their commercial success was exceptional, and the distribution over Europe so wide, that Mercator’s concept became the standard for many decades. The majority of his globes were made in Duisburg, Germany, where he had lived since 1922. After Mercator, Amsterdam became the centre of globe making.

Amsterdam, centre of globe making in the 17th century

Father and son Van Langren were active as globe makers in about 1580, publishing pairs of globes in two diameters, of approx. 32 and 53cm. The celestial globe is based on the observations of Rudolf Snellius, professor at Leyden University. A later edition (1589) of the large of the two globes was brought up to date by Petrus Plancius.

The States General in 1592 granted a privilege for the manufacture of globes for 10 years to Jacob Floris Van Langren which granted him the monopoly for globe making in the Dutch provinces. A similar privilege was granted in 1597 to Jodocus Hondius who had moved from London to Amsterdam. In London Hondius had been engraving the copper plates for a pair of globes designed by Emery Molyneux. Hondius had planned to start his globe making in Amsterdam. The Van Langrens challenged the decision of the States General, of course. The case was presented to the States by correspondence. In the archives we find a document by Hondius in which he specifies 14 items which lacking on the Van Langrens, but are present in his own globes. The verdict in this matter is not known, but in 1598 Hondius made a celestial globe. The protest of the Van Langrens was not unjustified when we compare the Molyneux and Van Langren globes. Molyneux’s celestial is an almost perfect copy of the Van Langrens, as in the case with the terrestrial one for which Molyneux made some additions based on new (English) discoveries. Copyright was an unknown concept. Government for a limited period of time granted privileges. Abroad these could not be enforced. This resulted in unlimited plagiarism and copying. Van Langren’s son left Amsterdam and set up business in Antwerp. His new 53cm. diameter pair was published in various editions until the middle of the 16th century.

The rivalry: Hondius-Janssonius versus Blaeu

One of the features of globe production in the beginning of the 17th century is the interaction between these two publishers and their successors. As soon as one of them brought a novelty on the market, the other immediately reacted by producing some thing with even more appeal. Blaeu’s edition of the 68cm. diameter pair of globes, however, was of such novelty that Hondius could neither match, nor surpass it.

Jodocus Hondius (born 1563), originated from Flanders but fled to London in 1584 where he worked with Molyneux. After his move to Amsterdam, he started the production of a pair of globes of approx. 35cm. diameter. Petrus Plancius was responsible for the design of the celestial globe. He introduced the constellations around the South Pole. This inclusion resulted from the Dutch voyages of exploration as earlier discoveries by the Portuguese and Spanish were kept secret. During the voyage of De Houtman from 1595-97 the “new” constellations were observed and described by a pupil of Plancius – who worked with Hondius – and Frederik de Houtman who was a pupil of a university professor who, in turn, stood in close contact with Blaeu.

Willem Jansz. Blaeu undoubtedly is the greatest among 17th globe makers. Born in 1571, He preferred to study mathematics, geography and astronomy over a position in the family business. This brought him to visit Tycho Brahe whom he assisted with astronomical observations during a period of some six months. Upon his return to the Netherlands, he settled in Amsterdam in 1598 and started a publishing company specialising in maps, books, globes and atlases.

During his stay with Brahe, he had copied the latter’s large celestial globe. This material served to make a celestial of 34cm, diameter for with the artist Saenredam provided the drawings of the constellations. The astronomical content and the highly decorative style made it the best and most modern of its time, but the globe ill-fated because Plancius and Hondius published their celestial globe with the new constellations around the South Pole only slightly later.

As Blaeu at that time was engaged in the production of the matching terrestrial globe, he was unable to prepare the publication of a revised edition of the celestial one (published in 1599). One year later Hondius published his terrestrial. The cartography of both globes is based on Mercator’s large world map from 1569 which, with information taken from the globes of Van Langren and Molyneux, was brought up to date to circa 1600. Both globes include the island of Nova Zembla and Spitsbergen discovered by Willem Barentz. Around the same time, Hondius issued a revised edition of his celestial globe for which he had carefully copied the drawings of the constellations on Blaeu’s globe!

It was only in 1603 that Blaeu could issue his revised edition of the celestial glob. He could not use the information that Hondius had obtained: the privileges granted to Hondius impeded Blaeu from copying Hondius scientific innovations, whereas Hondius was free to copy Blaeu’s artistic innovations.

Hondius died in 1612. His business was continued by his widow and later by his two sons. New editions of the 35cm. diameter globes were published, as well as a pair of 53cm. diameter in 1613.

This led Blaeu to start the preparations for the making of a pair with still a larger diameter of 68cm. This was to be the pair that would definitely confirm his fame as a globe maker. The celestial was issued in 1616, the terrestrial in 1617. The drawings of the constellations were designed in completely new style to again create a distinction from those of Hondius.

The firm of Hondius was unable to “respond” to this challenge. It published, however, a copy of these globes in reduced form, diameter 44cm., in 1622.

In 1622 Blaeu published a revised edition of the terrestrial glob which incorporated important discoveries like that of the Strait Le Maire (between the Terra del Fuego and Staten Island), a number of islands in the Pacific and the coastline of New Guinea.

Most of these additions were not included in revisions of Blaeu’s smaller globes, which is an indication that Blaeu considered his 68cm. pair his most important product.

Till the age of 50, Blaeu went without a family name: he was called Willem Jansz (or Guilielmus Janssonius in Latin). His neighbor and most important rival was Johannes Janssonius. As this led to unwanted confusion , Willem Jansz. in 1621 added the “family” name of Blaeu to his name. Blaeu (blue) he derived from the nickname “blauwe Willem” (blue William) of his grandfather. This means that all maps and globes on which the name “Blaeu” (varying in spelling) appears were published after 1621, even if an earlier year is given.

Engraver and publisher Petrus van der Keere ( Petrus Kaerius) was a brother-in-law of Hondius from whom he learned the art of engraving. He settled in Amsterdam and for his globes worked with Petrus Plancius (author of the celestials of Van Langren) and Hondius. Their co-operation resulted in three pairs of globes, the largest of these being of importance for the history of the discoveries of the area of the North Pole. East of Spitsbergen a number of islands and coastlines are drawn and labeled in Dutch. This implies that after the voyage of Barentz (1596) further Dutch exploratory voyages were undertaken. Their celestial show eight new constellations, such as Monoceros and Camelopardalis, showing that Plancius is the auther of these and not Jakob Bartsch. The star atlas of Bartsch, published 1624, lists the new constellations but it is obvious that he copied these from Habrecht’s globe, who in turn copied Plancius and Van den Keere’s work.

Amsterdam held the virtual monopoly of globe making. Globes made in other countries in general were imitations of globes made in Amsterdam. Among the first imitations after Hondius pair are those by de Rossi from Milan, Which differ only in date of publication (1621) and the dedication. Matthäus Greuter from Rome copied his pair of 49cm. from Blaeu and the celestial of his 26cm. pair from Van den Keere and the terrestrial from Blaeu.

Joan Blaeu and Amsterdam globe production until the end of the 17th century

Joan was the eldest son of Willem Jansz. He continued to publish the globes of his father without changes, with the exception of the largest pair (68cm.). The whole of the cartography underwent many changes because of the discoveries of Abel Tasman: Van Diemensland (Tasmania), New Zealand, some islands in the Pacific, and the western and southern coastline of Australia are added to the engraving. The islands of the (Dutch) East Indies are re-drawn according to recent observations. These changes resulted in the removal of the cartouches with the dedication and the legend.

In 1668 Joan acquired the copper-plates of the firm of Janssonius, which contained the three sizes of globe pairs by Van den Keere and Plancius. Earlier on, he had already obtained the plates of the other globes from Hondius effects. To these were added those of the lesser-known Amsterdam publisher Jacob Aerntsz. Colom who had published globe pairs in three sizes. These acquisitions enabled Joan Blaeu to offer a very broad assortment to the general public as shown by his sales catalogue of 1670 in which no less than ten pairs of globes are listed.

Until 1682, the son of Joan (Joan II) continued the business when he sold it to Jan Jansz. Van Ceulen who re-issued all of the globes in unrevised form. That he found buyers for these globes with cartography that dated some 70 years back is proof of the renown of the name of Blaeu.

Nationalisation of globe production in the 17th century

In 1666 the Acadèmie des Sciences was founded in Paris. This proved to be of great importance for the renovation of cartography. In The Story Of Maps by A. Brown, the author states that “scientific cartography was born in France under Louis XIV”.

The improvement of mapping and mapping techniques was one of the principal activities of the Academy. To improve sea charts, it was imperative to find ways to establish the geographical latitude with utmost precision. The Italian scientist Cassini Was invited to work for the Academy’s observatory as he had published (1668) a potential solution for the longitude problem. The achievement of the cartographic work of Cassini and his (grand)sons have been embedded in the floor of the observatory in the form of a world map with a diameter of 8 meter. Unfortunately this monument has not survived, but a reduced and enlarged version of it was engraved and published by Jean Baptiste Nolin in 1669. The influence of the Academy’s work on the mapping of the earth was tremendous. A very large number of maps were “drawn in accordance with the observations of the gentlemen of the Academy”. This phrase was the hallmark for excellent quality.

Innovations in globe production around 1700

The work of the Academy was of great importance for the commercial publishers of cartographic products. In the second half of the 17th century, the Netherlands lost its dominant position in map and glob production to French cartographers. The lack of innovation in material produced in the Netherlands is to be blamed. French publishers, in close co-operation with the Academy, could produce maps of an accuracy not found elsewhere. In the domain of globe making, however, the monopoly of Amsterdam was not replaced by a similar center elsewhere.

This increased interest was a crucial factor for the globe-making trade. The high demand no longer required national and international trade. The national market was sufficient to run a profitable operation. The effect of this development is that “national” globe makers become active in France (Paris), Italy (Venice), Netherlands (Amsterdam, again!), Germany (Nuremberg), Sweden (Stockholm) and England (London).

France

Until 1666 very few globes – imitations of Dutch-made ones in general – had been published in France. Around 1700, in the wake of the success of the Academy, a proper production started to develop with makers such as Bion, Delisle and Desnos. The output of these makers was comparatively small, as were the sizes of the globes they produced because they were comparatively lacking in technical expertise.

The French maker Nicolas Bion in his time was famous for the quality of his scientific instruments. He also produced globes in Sizes from 12 to 32cm. diameter. He published a manual on the use of the celestial and terrestrial globes, which can be considered the successor to Blaeu’s manual. Bion’s manual was frequently reprinted and was translated into German and English.

Guillaume Delisle was a pupil of Cassini and member of the Academy. He published (1700) two pairs of 31 and 15cm., respectively. The largest of these two bear the title “in accordance with the observations of (…) Academy of Science”. Delisle stripped his maps of all elements that were not confirmed by observation and was courageous enough to leave blank space for areas that had not yet been explored.

Diderot’s encyclopedia of 1757 carries an excellent contribution about the techniques of globe making. Didier Robert de Vaugondy, publisher of Diderot, started his production of globes in 1745 with a pair of 7in. diameter, followed by a pair of 19in. Plans to make a terrestrial globe of about 150cm. diameter were cancelled for lack of funding, but de Vaugondy did make the”Globe de Bergevin” with a diameter of 260cm.

Charles-Francois Delamarche was the first in France to successfully produce globes of 18, 24, 32 and 63 cm. for the mass market. To keep the sales prices low, he did not mount the globes in expensive brass meridian circles, but had these made from wood or papier-mâchè. The graduation of the circles was printed on paper strips.

Italy

A brief period of flourishing of globe production in Venice preceded the developments in France. Here the first widely recognized non-Dutch globe maker Vincenzo Coronelli (1650- 1718) was active. Father Coronelli may be regarded as a universal scholar from the Baroque, with a prime interest in geography. In 1648 he founded the world’s first geographical society. In his capacity as official cosmographer of the Venetian republic he published hundreds of maps and various atlases. His greatest fame, however, was achieved by his globe making. He supplied a gigantic pair of globes – of 400cm. diameter – to king Louis XIV of France. Once this project was completed he concentrated on publishing reduced versions of the pair in printed form. The first pair he designed was the largest, with a diameter of 108cm. Products of other globe makers have never matched this pair. It is the pride of many libraries. Between 1693 and 1697 further editions of his globes were published ranging in diameter from 82 to only 5cm. The latter are very rare.

Coronelli’s publication of his “Libri dei Globi” forms a separate chapter in the history of globe making. The book contains all of the gores for his range of globes and this openness towards the market is in sharp contrast with common practice at that time: publishers did not sell their gores, to avoid copying.

Coronelli’s activities, however, did not lead to the establishment of a proper Italian globe-making industry. It is only at the end of the 18th century that we find records of the work of globe maker Cassini who issued a pair with a diameter of 33cm. Although sets of printed gores are known, copies mounted on spheres to form globes are rare and found in Italian collections only.

The Netherlands

Gerard Valk and his son Leonard published newly-developed globes in the Netherlands in the same period as the boom in France. Their range of products included globes of 3, 6, 12, 15, 18 and 24in. diameter. The cartography is very detailed and is almost devoid of decorative elements. The significance of these globes lies in the fact that the cartography of the terrestrial is based on the data supplied by the French Academy and that of the celestial on the most recent source of information, the work of Hevelius, astronomer at Danzig (Poland). Hevelius designed a number of new constellations to fill the gaps between the Ptolemaic ones. The Valk globe makers were the only ones to apply Hevelius work to their globes. In England Hevelius work were not available: for this reason English celestial globes were designed primarily with the catalogue of John Flamsteed. The pairs of globes by Valk should be regarded as a genuine and fully new development in globe production, which justifies the Valks distinct place in Amsterdam’s cartographical history.

Germany

Some areas or cities have known short bursts of globe making activity while either before or after no (related) activity is recorded. This is different in the case of the city of Nuremberg. The city had known globe making activity since the 15th century, albeit not continuously and never on a scale comparable with Amsterdam or Paris.

Martin Behaim commissioned his Erdapfel in 1492 and Johann Schöner built his globes in Nuremberg in the 1th century. Although no globes of paper and plaster were made in the following 150 years, gold and silversmiths casted and hammered globes in precious metals, in forms such as globe goblets and beakers, decorated with maps copied from maps or globes made in Amsterdam.

In the first quarter of the 18th century, the globe-industry in Nuremberg was rekindled through the activities of George Eimmart, Johann Philip Andreae, Johann Baptist Homann and Johann Gabriel Doppelmayr in particular. Doppelmayr designed pairs of globes in three sizes: 32, 20 and 10cm. between 1728 and 1736. He made these in co-operation with the engraver and instrument-maker Johann Georg Puschner. The makers paid much attention to discoveries and explorers. On the largest of the terrestrial globe the routes of the voyages were drawn and labeled. A large cartouche in the Pacific is decorated with the portraits of the explorers, and crowned by a portrait of Martin Behaim who commissioned the first western terrestrial globe. That these globes were highly appreciated is shown by the long time they were available: a new edition of the largest of the pairs was published by Wolfgang Paul Jenig in 1791 as so many new discoveries – in particular the areas around the Pacific Ocean and Cook’s exploits – required an updated edition.

The last of the important glob-producers from Nuremberg is the firm of art dealer and engraver Johann Georg Klinger that published a variety of globes from 1791 onwards, the first pair with a diameter of 32cm. Later on smaller sizes followed. Under the name of C. Abel-Klinger Kunsthandlung the firm continued its activities well into the 20th century with the production of small globes for education and leisure.

Sweden

The Kosmografiska Sällskapet (Cosmographical Society) was founded in 1758. One of its objectives was the creation of a domestic production of globes and maps. One of the society’s members, the engraver Anders Åkerman (1723-1778) completed the first pair of globes, with a 1-foot diameter shortly after 1758. The design of the cartography was completely original and based on the latest observations. His largest pair of 59cm. diameter was published in 1766. The cartography of the terrestrial globe in particular is interesting because on it is one of the first modern maps which shows Strait Torres (between Australia and New Guinea, Which had been discovered in 1606, but had sunken into oblivion). Under the influence of geographer and society-member Torbern Olaf Bergman, a number of thematic elements from physical geography were added such as vegetation (forests), the directions of the trade winds, monsoons and sea currents.

The celestial globes are based on the star catalogue of Johan Flamsteed. For the southern hemisphere, information in the catalogue of De Lacaille (1756) is used. All 14 new De Lacaille constellations are drawn.

England

Very elegant globed for demonstration purposes typify English globe making in the 18th century on the one hand, and Pocket globes on the other. Between these two we find attractive table and library models, which were produced well into the 20th century.

We have already mentioned the work of Molyneux who designed various pair of globes engraved by Hondius. Around 1650, instrument and globe maker Joseph Moxon was active in London. He was trained in the firm of Joan Blaeu in Amsterdam and published an English translation of Blaue’s “Institutio Astronomica”. Moxon published globes in five sizes. The most important globe maker of this era, however, was George Adams, who had run an important instrument making business with his two sons George and Dudley in London since the 1750s. He built a great variety of physical instruments – among these the instruments supplied to Cook to observe the transit of Venus in 1769 – as well as orreries, planetaria and globes. The firm designed and manufactured globes with diameter ranging from 3 to 28in. The celestial globes were drawn according to Flemsteed. At the end of the 18th and in the 19th century a fair number of globe makers were active on the British Island, in London in particular. The most prolific publishers were William Bardin & Son, John Newton, John and William Cary and William & Alexander Keith Johnston (Edinburgh). The products of all these publishers excel in the detail of the cartography and in quality of the stands.

Pocket globes

The growing interest in matters of (natural) science led to the production of so-called pocket globes: miniature models that could be carried on one’s person to testify to the animation of its owner. The terrestrial globe is contained in a case made of two hollow and hinged hemispheres. The inside of the hemispheres carry the gores of the celestial globe.

Generally speaking this part of the pocket globe is an astronomical monstrosity as the common projection of the sky is eccentric: the sky as seen from outside the universe. If gores in this projection are fastened to the inside of a hollow sphere, a geocentric projection is suggested. It is rare for the makers of pocket globes to produce gores with a geocentric projection. The first ppocket globes may well have been produced in England. In the trade list printed in his “A Tutor to Astronomy and Geography” of 1659, Joseph Moxon advertises “Concave Hemispheres of the Starry Orb, Which serves for a case to a Terrestrial Globe, 3 inches Diameter, made portable for the pocket” at 15 shillings. In England, Moxon s regarded as the “inventor” of the pocket globe – although he may well have been inspired by one of Blaeu’s products –and he was certainly the principal promoter of this model of the blobe. In spite of followers outside England (Valk in The Nederlands and Doppelmayr in Germany), the pocket globe remains a typically English product from the 18th and 19th centuries.

Globes in Planetaria

In general, globe manufacturers sold their product in a form which allowed for relatively uncomplicated display and demonstration. This simplicity was not sufficient for scientific purpose however. For the understanding of the mechanics of astronomy, the planetarium – a mechanical model of the movement of the celestial bodies within the solar system – was an important tool. Further demonstration models were the tellurium and lunarium, which served to explain the movements of the Earth and Moon respectively. In these models, miniature celestial or terrestrial globes were mounted.

The 19th century: towards mass production of Globes.

The situation in the 19th century can be compared to that in the 18th: globes were being produced in all countries by countless companies, but the development in the 19th century is different, however, in two respects. Firstly, the production volume: in 1798 the lithographic printing process was invented which led to a much faster and cheaper production of the printed matter (gores and paper horizon rings) for the globes. After some decades, the development of chromo (colour) lithography resulted in even lower production cost, as the time-consuming hand-colouring of paper became a thing of the past. Larger output and lower cost enable schools to acquire a globe for every classroom, if not for evert student. A further advantage was that globe text could be printed in different languages.

The second aspect was that the concept of globes in pairs was abandoned. Geography and astronomy, which for centuries had been indivisible, now developed into separate branches of science. The concept of the terrestrial globe as a model of the earth is far easier to understand for a user of average education. Terrestrial and celestial globes were now being sold separately, and the production of the celestial ones decreased considerably. The terrestrial globe having lost its importance as an astronomical demonstration model, it was no longer mounted in a full meridian and horizon circle. The majority of globes were mounted in a (graduated) meridian semi-circle.

One of the best-researched globe maker – among the many which were active in the second half of the 19th century – is the firm of Felk. It was founded in 1854. The following year he offered three sizes of terrestrial globes and one celestial for sale. In his first year the output was 800 globes. The firm started the production of elementary astronomical instrument like planetaria, telluria and lunaria in 1860. The range of globes expanded continuously. The Austrian Ministry of Education, which obliged all schools to have a terrestrial globe, also prompted this. In 1873 alone, the company produced over 15,000 globes in ten languages. Eventually, the sales catalogue contained globes in nine sizes, in seventeen languages and in ten different models.

Today, the globes by Felk and many of the other 19th century globe makers are relatively rare, sometimes rarer than specimens from the 17th century, the reason being that these objects were so very common that no one considered them fit for preservation.

Epilogue

It is obvious that this contribution can only give a brief overview of 2,500 years of globe-making. Many subjects and even more globe-makers remain undiscussed. For further information, I would recommend the literature referred to beloe:

Der Globusfreund. Wissenschaftliche Zeitschrift für Globen- und Instrumentenkunde (Journal for the Study of Globes and related Instrument) (Vienna, since 1951) Annual publication of the International Coronelli Society for the Study of Globes and related Instrument, with contributions in German and English mainly.

Peter E. Allmayer-Beck (ed.), Modelle der Welt: Erd- und Himmelsgloben: Kulturerbe aus österreichischen Sammlungen (Vienna: Brandstätter, 1997)

Elly Dekker and Peter van der Krogt, Globes from the Western World (London: Zwemmer, 1993)

J.B. Harley and David Woodward (ed.), The History of Cartography, vol. 1: Cartygraphy in Prehistoric, Ancient and Medieval Europe and the Mediterranean (Chicago: University of Chicago, 1987)

Henry C. King, Geared to the Stars: The Evolution of Planetariums, Orreries and Astronomical Clocks (Totonto: University of Totonto, 1978)

Peter van der Krogt, Globi Nerrlandici: The Production of Globes in the Low Countries (Utrecht: HES Uitgevers, 1993)

Deborah Jean Warner, “The Geography of Heaven and Earth” in Rittenhouse: Journal of the American Scientific Instrument Enterprise 2 (1987), pp. 14-32, 52-64, 88-104 and 147-152 (on globe production in the United States).

Christie’s, London. Fine Globes and Planetaria, Tuesday 5 November 2002.